6

Learning Objectives

- What is metadata and how it works

- What is SEO and how it affects content creators

- How can content creators ensure the right market finds their content

Key Messages

- Content’s success is often a result of highly orchestrated behind the scenes labour

- Metadata and discoverability are political and reflect social biases

As content creators, it is vital to have your work easily found by your target audience. Luckily for us, systems to make sure the right people find the right content are in place. Without these systems, creating content would be akin to sending radio messages out into space with the hopes that someone, someday, might stumble across them by chance. Book stores used to be the place where people would discover a book, but the recent rise of online purchasing and algorithm-based recommendations has changed the way we discover books.

What is Metadata? How is it used for Publishing?

For publishers and other distributors of content, metadata is essential. But what is metadata? And what is its role in discovery? Metadata is the information, or data, that describes other data. While that may sound confusing at first, just think about it and you’ll see metadata everywhere. Take for example the index in a book—it is made up of data describing the book which itself is a form of data. Or maybe the name of a song as it appears on your music player—it describes the artists, song title, and even record title where the song is to be found. All of this is metadata. For publishers, the metadata that exists outside of the book is the most important way to describe it and ensure that it will be found by the public. Lets, for example, take a look at an Amazon page (or a library catalogue) for a book. Here it will tell us the name of the book, the subtitle, the author(s), how many pages it has, what is the size of the book, what categories it fits under, who the publisher is, what is its ISBN, etc.

The information that describes a book is used by those in the supply chain (from buyers to sellers to libraries) and needs to be as up to date, as accurate, and as consistent as possible. Like all systems, it is important to be consistent in using metadata as it will determine how easy it is to discover your content. Book names and author names need to appear exactly as they do on the book to ensure your work is accurately linked to—in fact, classification systems become more rigid and less adaptable online than they did in offline databases. For this consistency to take place, books are coded using the international system called ONIX for books, or ONline Information eXchange.

The Pitfalls of Classification and Metadata

Like all systems, systems of classification are created through socially constructed divisions and reflect both individual opinions and the social consciousness of the time. As discussed in the Bytegeist episode linked above, one of the worlds most popular systems to classify information—the Dewey Decimal system—is a great example of how systems relating to publishing are products of the material conditions of their existence. While the Dewey clarification succeeds in creating a system of discoverability it fails at creating an equal representation. If, for example, we look at the 200 categories in the Dewey decimal system which categorizes religion, we see that categories 200-289 are devoted to Christianity while 290-299 are left for every other world religion. Furthermore, it characteristics certain people such as lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender to a classification of abnormal sexual behaviour. While many libraries are changing these types of categories to reflect more modern ideology, or in some cases abandoning the system altogether, we can see inherent problems with classification. Even today within systems like metadata culture bias, outdated nomenclature, and political agendas affect how we categorize.

Metadata on the web

In much the same way, metadata plays an important role on the Web itself. Texts on the Web are coded with meta tags through the use of HTML. Meta tags help you can determine what information will be seen on different sharing platforms (such as the images and descriptions provided when sharing a page on Twitter, FB, or Google+), as well as helping search engines rank and find posts. In fact, without meta tags, you cannot reach readers organically. Through effectively using meta-tags to tags a post with key search words (see SEO below), you will increase the likelihood of your post being found by those who want it, and the likelihood of your post being found over others by ranking better.

There are three types of meta tags: the title, the description and the meta keywords tags.

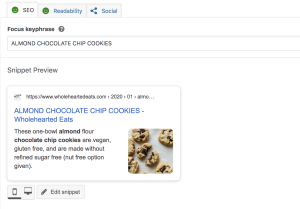

Above you can see how the content has been tagged to provide a desired title, excerpt, image, and focus keyword tags. This information will be used to create previews on social channels as well as help search engines pull and rank information.

What is SEO (and Why Does it Matter)?

For web content, discoverability is increasingly defined by SEO, or search engine optimization. SEO is a broad collection of practices aimed at “optimizing” the ease with which Web users can search for a given blog post, article, video, or other pieces of content. Practically speaking, this often comes down to making content as “Google-able” as possible.

SEO practices can touch on all aspects of digital content creation, from domain name selection and website design to social media promotion and even the writing process itself. Although it can be tempting to ignore these practices and focus instead on simply creating high-quality content, our so-called “attention economy” makes it difficult to do so. For many publishers—and for most content producers—ranking well in Google Search has become one of the primary ways to reach readers or retain financial stability. “Searchable,” for some, has become synonymous with “success.”

Dark Social

If we look back to earlier chapters we can see the myriad of ways our privacy is exploited and violated for political and monetary gain. However, there is one very large sector of the internet, that while using metadata, has managed to remain (mostly) safe from surveillance—and this area is called dark social. In 2012, Alexis Madrigal of The Atlantic first used the term dark social to describe “social traffic essentially invisible to most analytics programs”. Simply put, dark social is website traffic that comes from “invisible” shares through channels like messengers, email and text. In 2012, these channels were mainly email or Facebook Messenger. But now other private message apps are commonly used (a recent estimate, states that 12.1% of mobile users in the U.S. use WhatsApp, and 56.8% use Facebook Messenger), making them some of the top private channels through which content is shared and consequently, dark social is sustained.

In 2012, Madrigal found that dark social contributed to 56.5% of The Atlantic’s traffic, and they are not an anomaly. In a study of 150,000 sites in 2017, GetSocial found that 65% of traffic was a result of dark social sharing.

Website traffic from dark social is distinct from website traffic gained from sharing via a web-enabled medium. The difference lies in the mechanism of sharing and not the app or tool used. Let’s take the almond chocolate chip cookies metatag example (above) to see how traffic sources are attributed.

- Organic search traffic: You first Google ‘easy cookie recipes’ and click a search result to land on the recipe page of the Wholehearted Eats website—this is attributed as Organic Search traffic in Google Analytics or any other integrated website analytics tool.

- Social search traffic: You know your friend Annie loves chocolate chip cookies so you use the little Facebook sharer button to post the recipe link on Annie’s timeline. Annie clicks the link to view the recipe—this is attributed as Social traffic because referral metatags have been attached to the link to let the website know the visitor came from Facebook.

- Dark social/Referral traffic: If you send the URL for the cookies to Annie via an email, text, or direct message, you have shared it using dark social. An analytics tool will see her traffic as “direct” traffic even though the link was not typed into her browser. Because the analytics tool will not know where she got the article from, the referral traffic is attributed to the wrong channel.

Why should publishers care about dark social?

Publishers face opportunities in this vast sector of dark social sharing. Sharing is a significant part of the customer’s path to conversion and personal referrals are more likely to result in a conversion. Therefore, ignoring dark social could mean making ill-informed content production and distribution decisions. According to Hootsuite dark social can’t be ignored by publishers because 1) it is everywhere 2) it has a large impact on traffic 3) dark social data gives “detailed representation of consumers’ real interests”—that is, it allows access to targeted audiences 4) it reaches different (often older) demographics.

Yet in a time where user privacy is a rising concern and consumer exploitation is rampant, there is a balance that needs to be found between business and ethics. Some companies have already been exploring dark social’s potential using community influencers.However, dark social is still an untapped method for businesses to connect to their audience. The ‘best’ way to use it has yet to be found.

Questions

In this chapter, you learned about SEO, a range of practices that can affect all aspects of the content creation process.

- Can you think of any examples where optimizing content might have negative consequences—either for creators or for readers?

- What might be possible/different could you envision if we had perfect, high quality, complete metadata that was community-based? If we could get the publishers and Amazon to cooperate.

Also consider: What are the dangers of a single entity controlling metadata? What are other options? How could you democratize the use/creation of metadata?

Readings

- Dawson, Laura. 2012. What We Talk About When We Talk About Metadata. In McGuire, Hugh & O’Leary, Brian (Eds.). Book: A Futurist’s Manifesto. O’Reilly Media.

- Shatzkin, Mike. 2018. A changing book business: it all seems to be flowing downhill to Amazon.

- Shatzkin, Mike. 2018. The best ways to use Lightning are not widely employed yet 20 years in. The Shatzkin Files.

- Michel, Lincoln. 2016. Everything You Wanted to Know about Book Sales (But Were Afraid to Ask). Electric Lit.

- Parker, Sydney. 2017. Why Your Business Can’t Ignore Dark Social. Hootsuite.

Further Reading

- Shatzkin, Mike. 2016. Book publishing lives in an environment shaped by larger forces and always has.

- Shatzkin, Mike. 2014. The future of bookstores is the key to understanding the future of publishing. The Shatzkin Files.

- Friedman, Jane. 2013. The Importance of Metadata in Book Discoverability. Sprint Beyond the Book.

- Rhomberg, Andrew. 2015. Jellybooks: Tracking Reader Engagement for Better Marketing. Publishing Perspectives

Media Attributions

- Screen Shot 2020-01-18 at 2.28.57 PM